Why Trade Surpluses Don't Create Money

In our previous posts, we've established MMT's multi-level framework for analysing international trade, addressed theoretical critiques, reconciled apparent contradictions, and provided detailed balance sheet proof of our analysis. In this final post, we'll examine Steve Keen's latest claims about trade surpluses creating money and demonstrate why this fundamental misunderstanding undermines his entire critique of MMT's approach to international trade.

Keen's Explicit Claim: Trade Surpluses Create Money

In his forthcoming book "Money and Macroeconomics from First Principles for Elon Musk and Other Engineers," Keen makes an extraordinary claim:

"As shown in Chapter 2, 'The First Principles of Money' (page 8 et.seq.), a government budget deficit creates money. Similarly, a trade surplus—or more correctly, a surplus on the balance of payments—also creates money."

He further asserts:

"The logic in both cases is obvious: government spending increases deposit accounts while taxation reduces them; and import purchases reduce deposit accounts while export sales increase them. Therefore, at the level of the private banking system, and in the aggregate, the effects of a government deficit and a trade surplus on the money supply are identical—see Figure 44."

This claim represents a fundamental contradiction with Keen's previous agreement with Neil Wilson's "Anatomy of an FX transaction," which demonstrated that foreign exchange transactions ultimately reduce to exchanges of savings rather than money creation.

The Partial Picture: Analysing Keen's Figure 44

Keen's Figure 44 in his chapter (which readers can find in similar form in his published works on monetary economics) purports to show "the basics of money creation by government deficits and trade surpluses: private banks perspective." This diagram shows how export sales increase domestic bank deposits while import purchases decrease them, with the net effect being an increase in domestic money supply when exports exceed imports.

However, this figure presents only a partial view of international trade transactions by focusing exclusively on the domestic banking system's perspective. What's critically missing is the complete international accounting picture.

In Keen's Figure 44, we see only one side of the ledger—the domestic banking system. However, for every international transaction, there must be corresponding entries in the foreign country's banking system, where the exact opposite effects are occurring simultaneously:

Their import purchases (our exports) are decreasing their bank deposits

Their export sales (our imports) are increasing their bank deposits

The net effect in their banking system is a decrease in their money supply when our exports exceed our imports

When we consider the global financial system as a whole, no new net money is created through trade—it is merely redistributed between countries.

The Complete Picture: Balance Sheet Analysis

To demonstrate why Keen's Figure 44 presents an incomplete picture, let's examine the complete balance sheet effects of an international trade transaction. Unlike Keen's partial analysis, which only shows the domestic banking perspective, our analysis tracks all financial flows across all relevant sectors in both countries.

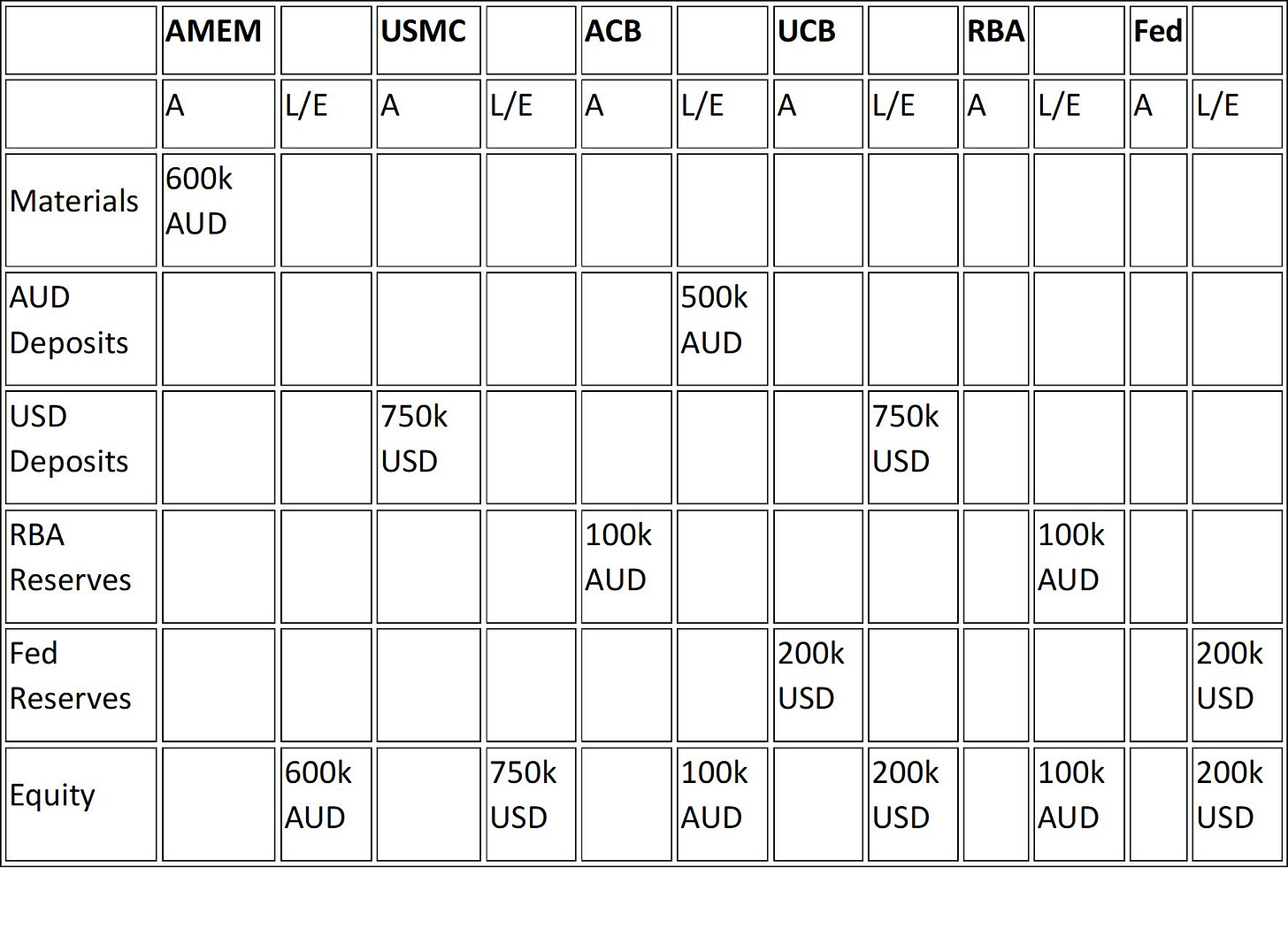

Initial Position Balance Sheet Matrix

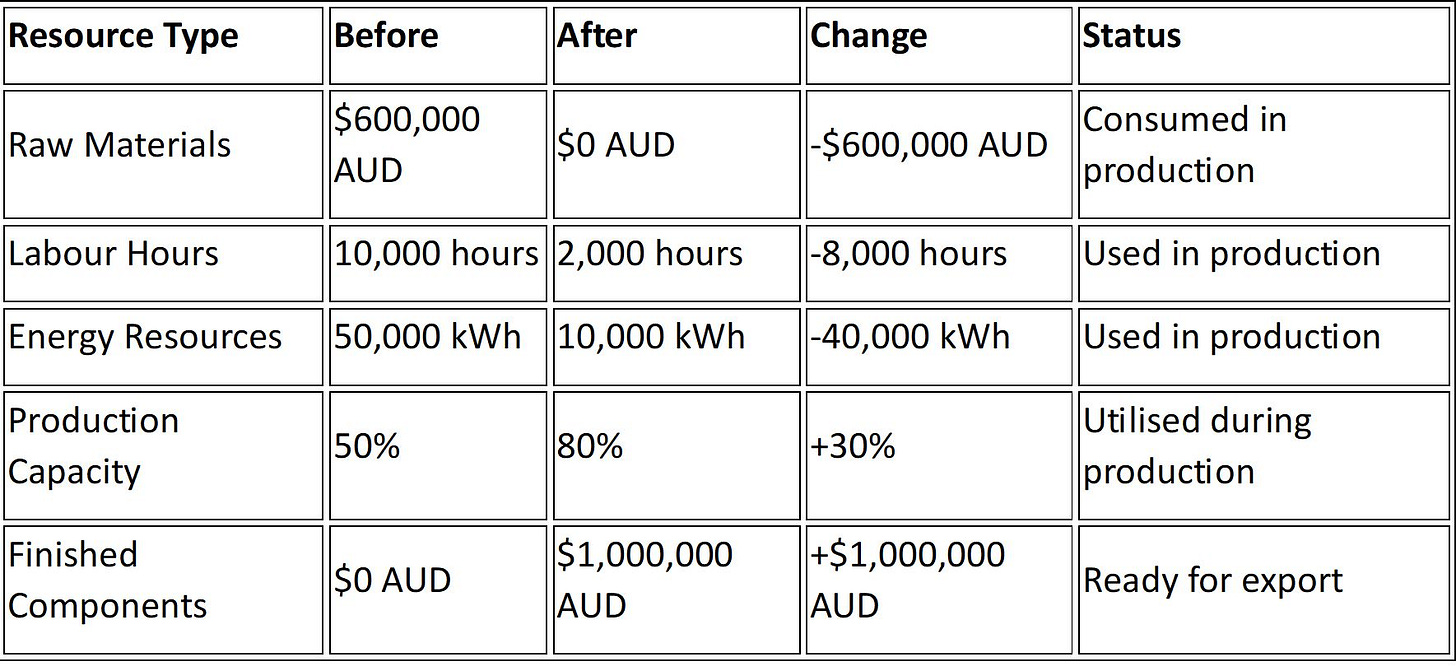

Real Resource Consumption in Production

When the Australian Mining Equipment Manufacturer (AMEM) produces goods for export, real resources are consumed:

No financial transactions have occurred yet - this stage only tracks real resource transformation.

Key Insight: Real resources (materials, labour, energy) have been consumed to create export goods. These resources could have been used for domestic production of other goods, representing the true "cost" of exports from MMT's perspective.

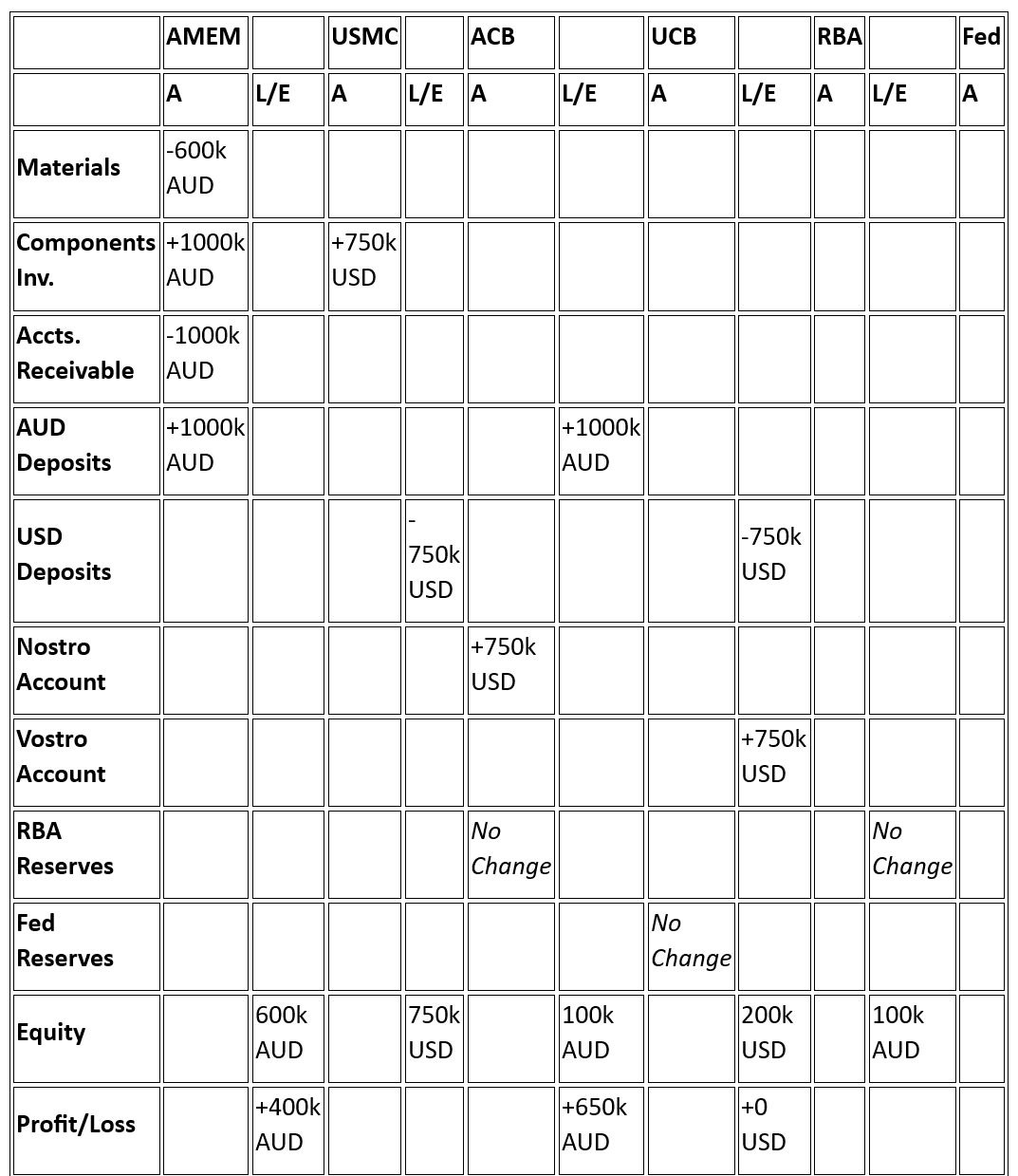

Final Settlement Balance Sheet Matrix

After all transactions are complete, the final balance sheet positions show:

Comparing the initial and final balance sheets reveals several critical insights:

No new net financial assets were created globally - The total quantity of AUD and USD remained unchanged

Existing currencies were redistributed between entities - AMEM gained AUD deposits, USMC lost USD deposits

Real resources were consumed in Australia - Materials, labour, and energy were used to produce export goods

The transaction involved exchange, not creation - Financial assets were transferred, not created

This comprehensive analysis directly contradicts Keen's claim that "the effects of a government deficit and a trade surplus on the money supply are identical."

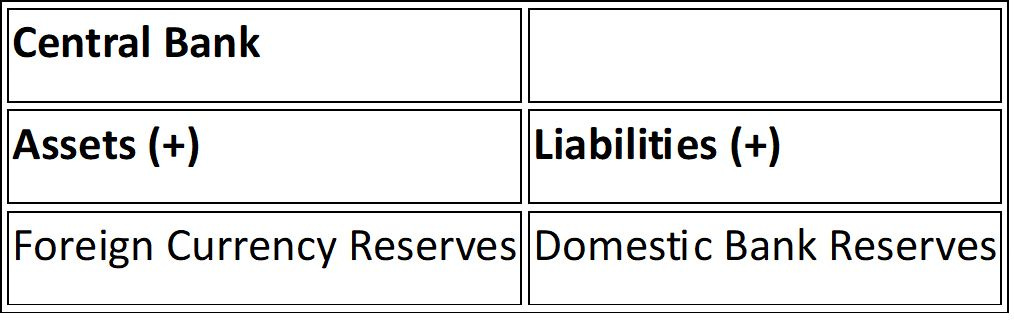

The Central Bank Perspective

Keen attempts to extend his analysis by showing how trade surpluses affect central bank operations, stating:

"A trade surplus adds to Reserves by increasing the Central Bank's holding of foreign reserves."

This description reveals another critical misunderstanding. The central bank doesn't automatically acquire foreign currency from exporters--foreign currency earnings typically remain in the commercial banking system unless specific policy interventions occur. Any central bank accumulation of foreign reserves represents a policy choice, not an inherent feature of trade surpluses.

More importantly, these operations involve exchanging one existing asset (domestic currency) for another (foreign currency), not creating new net assets. This is fundamentally different from government deficit spending, which creates new financial assets without corresponding private sector liabilities.

Balance Sheet Mechanics: Foreign Reserves vs. Fiscal Deficits

To make this distinction crystal clear, let's examine the precise balance sheet mechanics of both operations:

Foreign Reserve Acquisition (Asset Swap)

When a central bank does choose to acquire foreign reserves following a trade surplus:

This represents a mere asset swap because:

The central bank creates domestic currency reserves (a liability)

In exchange for foreign currency assets (claims on foreign entities)

The private sector surrenders one financial asset (foreign currency) and receives another (domestic currency)

No net financial wealth is created in the domestic private sector

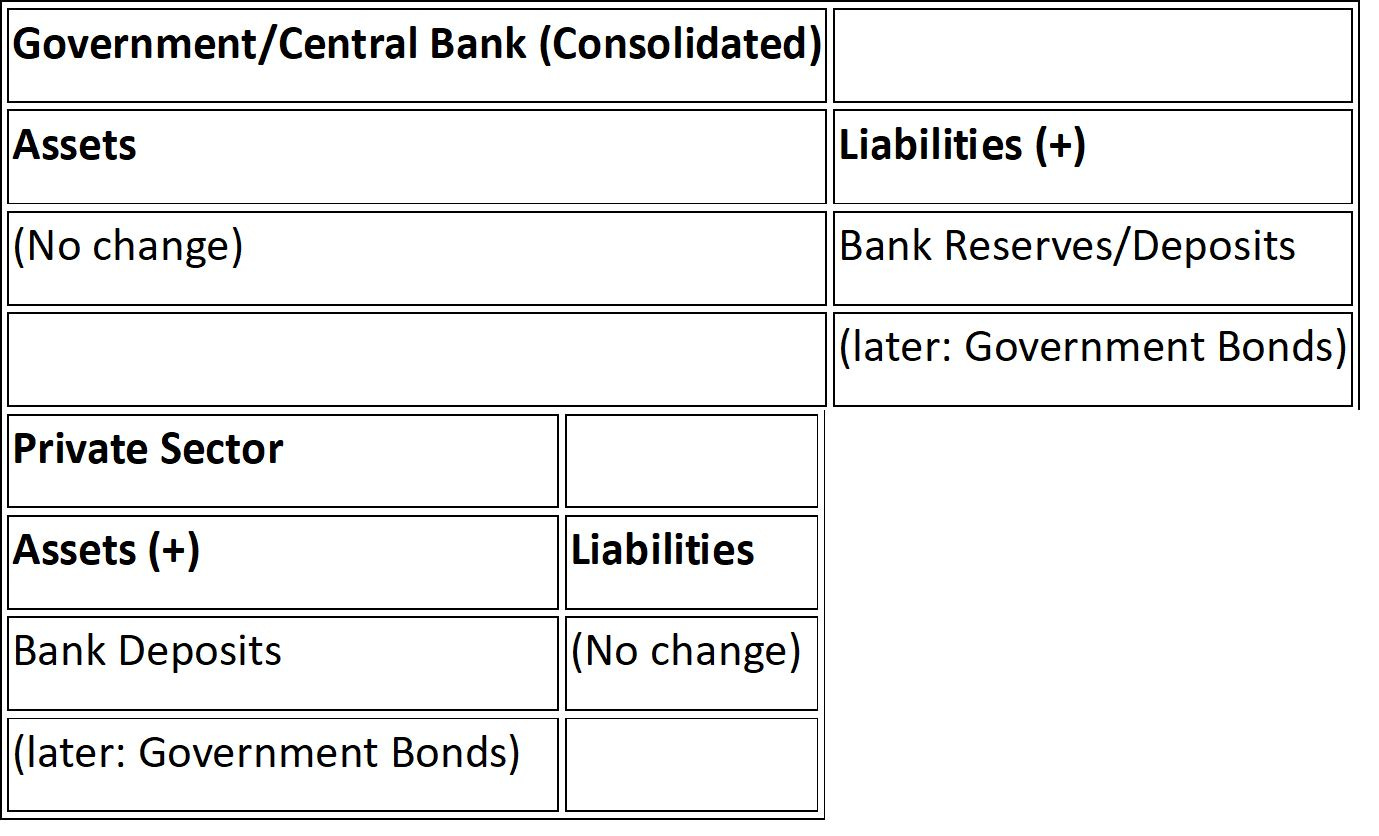

Fiscal Deficit (Net Financial Asset Creation)

In contrast, when the government runs a fiscal deficit:

Government/Central Bank Consolidated Balance Sheet:

This creates genuine net financial wealth because:

Government spending creates bank reserves and bank deposits without requiring the private sector to surrender any financial asset

These reserves/deposits (or bonds after bond sales) represent net financial assets for the private sector

The private sector's financial wealth increases by the exact amount of the deficit

The fundamental difference lies in what the private sector must surrender:

In trade surplus/central bank operations: The private sector exchanges foreign financial assets for domestic ones

In fiscal deficits: The private sector provides real goods and services (not financial assets) in exchange for new financial assets

While trade surpluses may generate profits for exporters, the central bank's acquisition of foreign reserves merely converts the form of existing financial assets from foreign to domestic currency. This operational reality directly contradicts Keen's claim that "the effects of a government deficit and a trade surplus on the money supply are identical."

The Fundamental Difference: Creation vs. Redistribution

Keen's error stems from conflating two fundamentally different processes:

Government Deficit Spending:

Creates new financial assets (bank deposits) for the private sector

These new assets have no corresponding private sector liabilities

Increases the net financial worth of the private sector

Represents true money creation

Trade Surpluses:

Redistribute existing financial assets between countries

Every financial asset gained by one country is lost by another

Do not increase the global supply of financial assets

Represent redistribution, not creation

Keen acknowledges this difference elsewhere when he states:

"A trade surplus or a trade deficit is different because, in the aggregate, for all countries the sum of all trade deficits is zero."

Yet he fails to recognise how this fundamental difference undermines his claim that trade surpluses create money in the same way as government deficits.

The Simulation Model

Keen's simulation model shows that "the 1% of GDP trade deficit transfers 1/3rd of the money created by the US government deficit to the Chinese economy." This statement inadvertently reveals the truth: trade doesn't create money—it transfers existing money between economies.

His model shows China growing faster than the US because China is capturing a portion of the money created by the US government deficit. This is redistribution, not creation, yet Keen persistently conflates the two processes.

Resolving the Contradiction with MMT's Multi-Level Framework

MMT's multi-level framework resolves this apparent contradiction by properly distinguishing between:

Financial flows: Trade redistributes existing currencies but doesn't create new net financial assets globally

Real resource flows: Exports represent real resources leaving the domestic economy (a real cost)

Capacity utilisation effects: Export production can utilise otherwise idle capacity (a potential benefit)

Employment impacts: Export industries can provide employment (a potential benefit)

Sectoral balance implications: Trade surpluses improve private sector financial positions within a country (a financial benefit)

By maintaining analytical clarity about which level we're addressing, we avoid the confusion evident in Keen's analysis.

The Implications for Keen's Critique of MMT

This fundamental misunderstanding undermines Keen's entire critique of MMT's approach to international trade. If trade surpluses don't create money in the same way as government deficits (as our analysis proves), then his argument against MMT's "exports are costs, imports are benefits" framework collapses.

MMT's statement that "exports are costs, imports are benefits" refers specifically to the real resource level of analysis—the physical goods and services that move between countries. This statement is entirely compatible with recognising that:

At the firm level, exports can increase capacity utilisation and profitability

At the employment level, export industries can provide jobs

At the sectoral balance level, trade surpluses (current account surpluses) improve private sector financial positions

However, none of these benefits change the fundamental reality that exports represent real resources leaving the domestic economy that could have been used domestically.

The Simple Truth Behind Complex Accounting

One notable aspect of this exchange is how a straightforward MMT insight—that exports represent a real resource cost while imports provide real benefits—required extensive balance sheet modelling to address Keen's critique. This highlights something important about economic discourse:

What requires complex accounting to demonstrate to some can be intuitively obvious to others.

The balance sheet matrices we've constructed, with their nostro/vostro relationships and multi-level analysis, ultimately confirm what MMT has expressed in simpler terms all along: when a nation exports, it uses domestic resources (labour, materials, energy) to produce goods that foreigners, not domestic residents, will consume. This represents a real resource cost from the national perspective, regardless of the financial benefits that accrue.

Perhaps Keen's misunderstanding stems from requiring elaborate double-entry proof for what is, at its core, a straightforward insight about resource utilisation. The extensive modelling ultimately validates the concise verbal explanation: exports cost real resources that could have been used domestically, and the purpose of accepting this cost is to finance imports that provide greater benefits than those foregone resources would have.

Conclusion: The Power of Analytical Clarity

Keen's contradiction—claiming both that FX transactions reduce to exchanges of savings AND that trade surpluses create money like government deficits—reveals the importance of analytical clarity when discussing international trade.

MMT's multi-level framework provides this clarity by:

Distinguishing between real resource flows and financial flows

Recognising the different impacts at various levels of analysis

Maintaining consistency across these levels

Avoiding the conflation of redistribution with creation

By properly understanding the difference between money creation and money redistribution, we can develop more effective trade policies that serve the public purpose rather than narrow financial interests.

The words are simple because the fundamental truth is simple: exports cost real resources that could have been used domestically, and the purpose of accepting this cost is to finance imports that provide greater benefits than those foregone resources would have provided.

Keen's latest contradiction only strengthens the case for MMT's sophisticated multi-level approach to international trade—an approach that properly accounts for both real resource flows and financial realities while avoiding the fundamental error of confusing redistribution with creation.

As nations navigate the complex trade relationships of 2025, with intensifying economic bloc formation and persistent domestic inequality, the distinction between money creation and redistribution has practical implications for policy. The analytical clarity provided by MMT's multi-level framework offers valuable insights for addressing today's challenges, including managing the distributional impacts of strategic decoupling and implementing industrial policies that serve the public purpose within an increasingly multipolar global economy.

Where to Go From Here

If you've found this analysis valuable:

Share this article with others interested in alternative economic perspectives

Join the conversation in the comments—I'd love to hear your thoughts

•Subscribe for free to receive my weekly economic insights

Have a specific economic question you'd like me to address in a future post? Let me know in the comments!

Unmask Economics With Me

My draft papers aren't polished academic work—they're attempts to understand economic theory correctly, asking questions like:

What if we've completely misunderstood how taxes work? (Strategic Preparatory Financing)

What if the economy isn't about equilibrium but buffer stocks all the way down?

What if informal networks are the foundation of how economies actually function?

As a paid subscriber ($15 AUD monthly/$120 AUD annually), you get:

Exclusive access to my complete Draft Papers Library

Full archive access and community participation

Financial Wellness Resources (Anxiety-Busting Posters & Financial Tips)

For dedicated supporters, the Founding Economist Circle ($240 AUD annually) offers:

All paid benefits plus recognition in research papers

A dedicated Founding Members page

Occasional opportunities to provide input on research directions

No promises of getting rich. No pretense of having all the answers. Just real attempts at understanding how this complex system actually works.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider buying me a coffee by pressing the button below.

Great post! Just to play devil’s advocate though, Keen might be saying that the trade surplus increases the stock of financial assets in the country that is the net exporter. That would be correct, unless I’m missing something? In that way it is similar to the government deficit increasing the stock of financial assets in that country

Great analysis, outstanding